Glossing over Africa’s image

There is a growing tide of activities taking place in Northern Ireland which aim to project a new image of Africa. It is hoped that the European Commission funded project: Images and Messages of Africa from an African Perspective will change biased perceptions in Northern Ireland. African Diaspora organisations in Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland and Slovenia were awarded a sizeable amount from the EU coffers to reverse the trends.

It is difficult to be precise about the extent to which Africa is misrepresented in Northern Ireland. Young people in schools, colleges and universities have their curriculum education on Africa – but whether that is limited or appropriate is another question.

The adult population of Northern Ireland have different insights about the continent of Africa – either unrestricted in prejudice or wholly organic, and perhaps a good grasp, depending on which political ideology one subscribes to. The total sum of these ways of thinking about Africa cannot be dismissed as speculative or mere biases, truths or untruths.

But there is a degree of some home truths. Col. Muammar Gaddafi is still performing his debauchery standing tall like a Greek colossus watching over his mere mortals, the Libyan people. For those who were born in Mogadishu, roughly two decades ago, predominantly what they have known in their entire life is a war torn country called Somalia.

Around the globe technology has essentially driven the direction of the devastating war in the Democratic Republic of Congo, given its useful strategic position as the key supplier of Coltan, a mineral ingredient necessary for the production of electronic consumer products like mobile phones.

Other numerous narratives that describe Africa in these pictorial ways can therefore not be dismissed as sheer Western media bias and what critics like Rotimi Sankore call “development pornography.” The killing of an elderly couple by villagers in Nyalenda just outside Kisumu town in Kenya this week, because they were accused of practising witchcraft is a prehistoric, ice-age homicide.

Yet the villagers were reported to be glorifying their mission of cleansing the place of witches. If Africa accepts that this image is true of its depiction, then things can move forward.

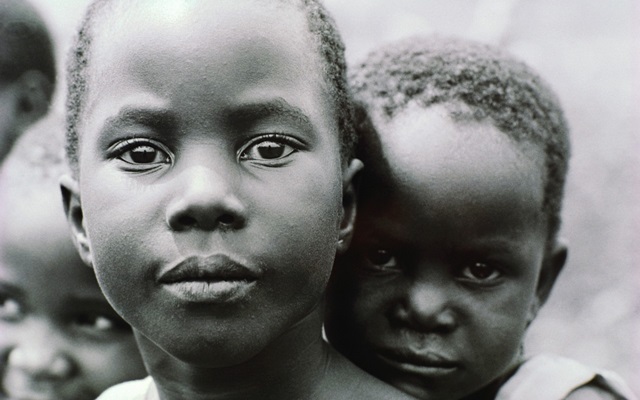

According to Sankore, a development journalist, this kind of pornography is mainly practised by non-Africans, usually non-black, who show graphic, iconic skeletal images which NGOs exploit so they can raise money for their long-term ventures in Africa. He even goes further to describe this dynamic of fundraising as provocative to the extent that it even causes minimum arousal to its victims, the paying Western public.

Of course it is important to show that poverty exists on the streets of Brussels, Delhi, Derry, Durban and Dublin. This is presumably the picture the EU dreams of – an equal message: poverty is widespread and Africa is not the only victim.

The world wars will also remind us that conflict on the other hand, has hurt Europe more than any other parts of the world put together. If there were role reversals and Africans were analysing the primitive Europe of the 1940s, would the EU have had the same focal intervention, to attempt to remove the biases?

Afro-centric critiques, bystanders or travellers in this boat that is challenging and demystifying Africa through an African perspective, have a big mountain to climb. Who is their audience? Are they listening? Do they care? Have they a supreme obligation to take part in this re-education or is their liberal choice to subscribe to a media house they like, an individual freedom that should not be curtailed by the EU?

To call a spade a spade, Africa’s poverty and other social maladies have primarily political solutions which should really, emanate from Africa and spread like bushfire from the periphery to its capitals.

For some peculiar six-decade post-colonial reason, that moment has not arrived yet. This is why the EU and other organisations are finding it easy to compel people to listen to this benign message that Africa is in trouble, this time outside the continent itself.

Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair experimented with a similar benevolent directive to development agencies telling them about his pet subject, the Commission for Africa. Without giving any special chronological detail, Blair had to do something about Africa while he was keeping Afghanistan and Iraq aflame.

The Commission for Africa set up in 2004 was for that reason a massive coup for Blair. The roll call included known names in social justice activism like Bob Geldof, economic gurus such as Blair’s own successor Gordon Brown and a number of African leaders, business people and international mandarins.

Having attended its inaugural meeting in Nairobi as a facilitator, the kind of consultations between the lead partner the UK and the periphery people, the Africans, reminded me of a parent-child relationship. To put it in a nutshell, there was nothing that the periphery did not speak of; she remained naked and ready for further exploitation. This was Africa at its better, trying its best to beg the donor country through Tony Blair’s baby project.

To this date, the Commission for Africa is still tossing out annual reports which are only read in that little club at the top. In 2010, it launched a new political idiom, our common interest. The report reminds readers that the Commissions see that the only solution to Africa’s poverty is by Africans.

It is ironic that a myriad of conferences have to be held in order to have this consensus. Of course this is an obvious claim but their conditional claim is that Africa needs to keep borrowing, doubling of aid should continue and that without the Commission for Africa, the Gleneagles Agreement would not have seen the cancellation of debt of over $100 billion owed by Africa.

But the opposite argument is that what is happening is clearly an age-old phenomenon known as, stereotype. If this is taken as a universal unit, then Africans in the European Diaspora can begin by asking themselves one question – are some of those biased descriptions about Africa factual? And if there is only one true way of measuring these truths, through photos, then why is there any need to care about reversing some elements of truth?

One could accurately say that the only way some of these images of Africa can be sanitized is by Africans themselves admitting them and henceforth, being dynamic, changing some of the intractable stereotypes.

This is not to say that the EU funded methodology is inappropriate, but the end result is baseless if the radical admission of the truth and acting upon it is not in itself a consequence. The African Diasporas in Europe need not be obsessed with removing these images as though they were some eyesore graffiti.

Instead, they should responsibly open a debate with institutions and non-governmental actors to report more of the good and bad news on Africa, but not simply the good news. Putting the good news at the top of the hierarchy at the expense of truth is very suicidal for the long term image of Africa. So the EU effort can be construed as a welcome development but how is it being done, what are its goals, are there any clear objectives other than simply reversing the popular image of Africa?

In Northern Ireland, when taking on the post-conflict discourses, migration included, there is little room for radical persuasion. Notions of a shared future fill the air, what future and whose future is the real question. The Holy Grail that no one wants to touch is cultural perceptions and images of migrants and where they come from around the world.

Those who are attempting to address this intellectually also risk being labelled chip-on-their-shoulders activists – in other words, merchants of political correctness gone haywire. A radical debate is never far away even if it is tactfully covered by the centre. The periphery will always have their voices heard, one way or another.

Elly Omondi Odhiambo was former Chair of the African & Caribbean Association of Foyle, 2007-2009